Save the Whales! Save the Plastic Bags?!?

Plastic bags are an environmental headache, but finding a feasible replacement for this single-use disposable product that customers will use has proven to be a considerable challenge.

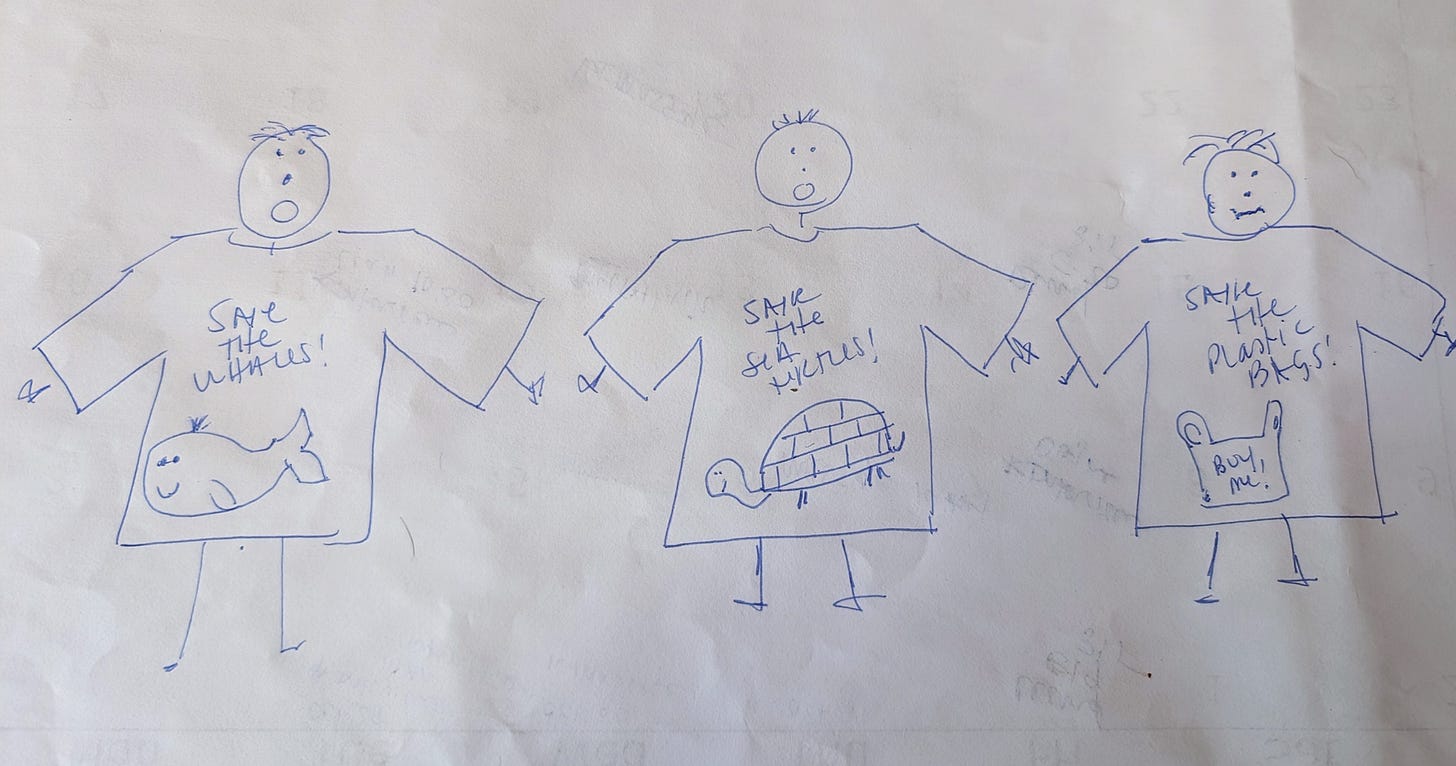

This post’s title comes courtesy of a political cartoon I saw some years back. Three people are standing together wearing message T-shirts: The first reads “Save the Whales”; the second, “Save the Sea Turtles”; the third, “Save the Plastic Bags”. The whale and sea turtle advocates scowl at the plastic bags guy (as some of us would), while others may be perplexed. The idea that plastic bags need to be ‘saved’ surfaced when environmentalists began pressuring (usually) local governments to ban markets from offering plastic bags, citing concerns about pollution. Not surprisingly, the plastics industry swung into action to protect its market, anticipating other single-use products were also heading for the chopping block.

The World Counts (and apparently every other source) estimates the average use time of a plastic bag at 12 minutes. The researcher in me is skeptical about the accuracy of this figure. (So many variables to consider: Is this self-reported? Does this include use in developing countries? Is this all plastic bags of all sizes, from convenience stores to farmer’s markets to mega-marts?). Regardless of exactly how long a plastic bag is used, the point is to show that we take this single-use, disposable product for granted, giving little thought to the object that conveys products from one location to another. This issue is particularly pressing with the COP 26’s warning about the critical need to reduce carbon emission outputs to reduce the planet’s increasing temperatures.

Plastic bags have made their way around the world, becoming an environmental headache in every country. The onus falls on governments to implement policy controls, as businesses have little incentive to irritate their customers by denying or charging them for bags. Faced with increasing plastic waste and growing concerns about microplastics in the water, countries took steps—to varying degrees—to control the manufacture, use, trade, and import of single-use plastic bags. By 2018, the UNEP reported that 127 countries had implemented measures to reduce plastic bag usage. Most notable at the time was the push by several African countries.

Rwanda might have one of the toughest laws, confiscating plastic bags from tourists upon entry into the country. A small country highly dependent on its tourism industry, the government has a compelling interest in minimizing the blight of plastic bags on its landscape. With a similar incentive, coupled with the huge challenge Global South countries have coping with managing waste, Kenya enacted a ban in 2017. Initially the government had a high success rate, with popular support for the measure. The policy, however, caused two unexpected consequences. Though shoppers switched to reusable bags, they failed to use them long enough before dumping them into the landfill. Not surprisingly, policymakers should have also anticipated that a thriving smuggling ring from neighboring countries would fill the gap, once licit bags were taken out of circulation.

I’m amazed every time I visit sub-Saharan Africa, as both men and women regularly carry an array of goods to sell and purchases on their heads (and have amazing posture as an added benefit). I was nonplussed to see this in cities in Ghana, as it’s much more common in rural areas. Everything from bunches of leafy green vegetables, stacks of wood, and sugar cane perch atop people’s heads as they walk along the road. When they can’t be easily bunched, the most common conveyance is a large plastic tub or items bundled in cloth.

Outside of Africa, I haven’t seen people do this much except in rural areas of South America and Southeast Asia. Many countries in these regions are on the higher end of economic development, so more people have access to motorized vehicles (from motorbikes and tuk-tuks to automobiles and public transportation). Though this is just a working theory that those who walk are less likely to rely on single-use bags, there seems to be a correlation between disposable means of conveyance and access to motorized vehicles.

What Are Our Options?

Our recent podcast episode of Bags Don’t Litter, People Litter got me thinking about the history of the paper bag, which developed along with industrialization as people’s shopping habits transformed. The Smithsonian Institution holds one of the original machines invented by Margaret E. Knight, who perfected the original design created in 1852 that mass-produced paper bags. The paper bag even has a place at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC. (But is it art?) The plastic bag displaced the paper bag when supermarket chains realized how much less expensive, more durable, more compact, and easier to open and fill these nifty little things were. Soon thereafter began the debate about banning bags. Whether paper or plastic, the attempt to ditch these has proven largely ineffective in the U.S., where lobbyists have earned their big bucks to keep them in circulation.

The focus on bags is usually whether paper or plastic is less harmful to the environment, often willfully ignoring the fact that both have environmental consequences and that there are other options. I often wonder why shoppers are resistant to giving up plastic bags—or paper ones, for that matter. Having customers bring their own bags, baskets, or boxes does not seem like a huge inconvenience. When Aldi opened its doors in the U.S., Americans were miffed at having to pay for bags at checkout. The German retailer pushed the envelope even further with its 2024 announcement to also stop selling plastic bags in its stores. With its growing market share in the U.S., Kroger and Walmart followed suit with similar intentions to ditch plastic bags.

Some think biodegradable and compostable bags are a better option. Wrong. First, both are still single-use, which is one reason why countries like Canada have included these in its ban. Another is that people assume that they can go in with recyclable materials, but they cause the same headaches in MERFs getting stuck in the machinery as plastic bags. The Canadian government hopes to tackle the underlying bigger issue of reducing dependence on disposable plastic products.

I expect someone in Ottawa also made this fourth argument, which is that there is a big difference between the conditions under which bags that are either biodegradable or compostable need to disintegrate. Though India banned plastic bags in 2022, it has allowed for the continued use of biodegradable and compostable bags that can be proven to degrade within 180 days. Perhaps the rationale is that it’s a lot hotter in India than Canada and it’s better to have organic waste than non-degrading plastic waste strewn about the countryside. Biodegradable and compostable bags don’t pose the same issues as the (seemingly permanent) blight of plastic bags on the landscape, ending up in waterways, or taking an eternity to degrade (well, sort of, as they never fully degrade; they just disperse microplastics into the water and soil). But these bags require specific conditions under which to effectively degrade.

The Debate over Reusable Bags

While quaint and completely practical for market days in towns in Europe, woven baskets aren’t likely to make a comeback as a replacement for shoppers at the local supermarket. Some stores provide leftover cardboard boxes for customers, but that cannot be upscaled to meet daily demand. But the fact remains: We buy stuff—sometimes a lot of stuff—and need to get it home. The most viable option appears to be reusable bags.

Not wanting to bear yet one more personal responsibility to tackle the environmental disaster we’ve collectively created, people take out their frustration on cloth bags. Every possible issue is raised when debating whether it’s better to replace single-use bags with reusable cotton bags. How bad is this option for the environment? How many times do these need to be reused to make them worth the trade-off? How much landfill space do they take up? These questions didn’t stop people from going crazy for Trade Joe’s bags. The upscale ‘small feel’ supermarket hit paydirt in February 2024 when their tiny canvas totes went viral in Japan, quickly infecting U.S. shoppers. Overall, I feel like this debate is yet another diversionary tactic on the part of the plastics industry, colluding with fossil fuel producers and retail corporations, to obscure the behemoth single-use disposable products dilemma they’ve gotten us into.

Enter: The Recycled Polypropylene Bag

One developer of the recycled polypropylene bag, Polystar, would have us believe that these are the answer to all of our problems. Made from recycled plastics, these lightweight bags can be reused and recycled when they wear out. Retailers like to sell these at their check-out counter with their names splashed across the side to serve as portable billboards. Polypropylene bags offer a way to repurpose the tons of single-use plastics humans devour every day. While these bags are a durable replacement for single-use bags, they seem like more of a way to permit the continued use of disposable plastics. However, in the short term, humans need some way to deal with the mountains of plastic we consume daily, so these bags at least help to offset our addiction to disposable plastics and offer a way to forego “Paper or Plastic?” at the check-out counter.