A Renewed Life on Glass

Glass bottles and jars should be banned from landfills. This infinitely reusable substance deserves to be saved from the crypt to live another day.

In my Sustainability class, a student’s grandfather had passed away and her family was preparing to sell his house. While talking about the (growing collection of) Rs of sustainability—Reuse, Reduce, Recycle, Repair, Repurpose, and maybe even Redistribute should be in there, as donating to charity shops constitutes redistributing unwanted, but usable goods—this student mentioned that her grandfather had a lot of stuff, including numerous collectibles, but they just didn’t have the emotional capacity or time to deal with the situation, so they ended up hiring a dumpster and throwing out most of the contents.

Around the same time, my spouse and I were thinking about relocating, which is when I came across Kept House. Greg Pipkins and his wife, Jamie, started the business after organizing their own estate sale. Both with backgrounds in non-profit organizations and a passion for the environment, their objective in emptying a home is to keep as much of its contents out of the landfill as possible. I recently interviewed Greg, hoping to inform people of the usefulness of an estate sales company.

Skip the Landfill and Head for the MERF

Landfills are frequently confused with dumps. Having visited both, I can attest that they are a world apart. Landfills are heavily regulated disposal sites, many of which have 'regenerated' and ‘reclaimed’ (more Rs for the list) the land in developed countries for golf courses. Dumps are typical in developing countries where areas near cities are sectioned off, walls built, and garbage dumped, as I saw in Maputo, the capital city of Mozambique. Efficiently harvesting anything usable from the waste stream and lacking regular waste collection, people seem to tacitly agree on a place to dump whatever cannot be of use.

Glass can be infinitely recycled; the quality doesn’t degrade through the process like cardboard, paper, and plastic. Along with metal cans, cardboard, and newspapers, glass was one of the first items collected for recycling. In a Materials Recovery Facility (aka, MERF), glass gets crushed and sold off to glass and fiberglass manufacturers. In countries lacking organized recycling collection and MERF processing, the journey is a bit different.

Ngwenya Glass Factory

The Ngwenya Glass Factory in Eswatini (formerly Swaziland) was started by a Swedish aid organization in 1979 that sought to keep alive the Swazi’s traditional handicraft of glassblowing. After a rough patch, the factory grew into a local fair-trade mainstay, employing 70 people earning a living wage. Built on sustainability principles, Ngwenya collects glass throughout the tiny country, paying per kilo for clean glass. Their furnaces run on recycled fuels from KFC cooking oil and discarded engine oils. Proceeds from their glass rhinos and Elephant Fund promote wildlife protection. They sponsor community service projects from road clean-ups to school programs to raise awareness about the environment. Their shopping complex houses other social enterprise businesses selling ethically made products including batik-dyed fabrics, woven goods, chocolate, and a variety of traditional Swazi foods like chutneys and honey. It’s pretty impressive what this NGO has grown into since its inception, benefitting from the initial European support to build an impressive export business of handmade and mouthblown glass.

Cedi Bead Factory

Unlike the slick marketing that Ngwenya can afford thanks to initial aid from an international NGO, an Internet search for Cedi Bead Factory only returns results of reviews, videos, and photos from tourists venturing to Koforidua, a village in western Ghana. While Eswatini benefits from its proximity to the Emerging Economy and phenomenal destination of South Africa, Cedi depends more on domestic sales. Beads play an important part in Ashanti culture, as gifts and are significant in rites of passage of baptism, puberty, weddings, and funerals. Its long family history of glass bead making has earned it notoriety, making it worth the visit or call to place an order.

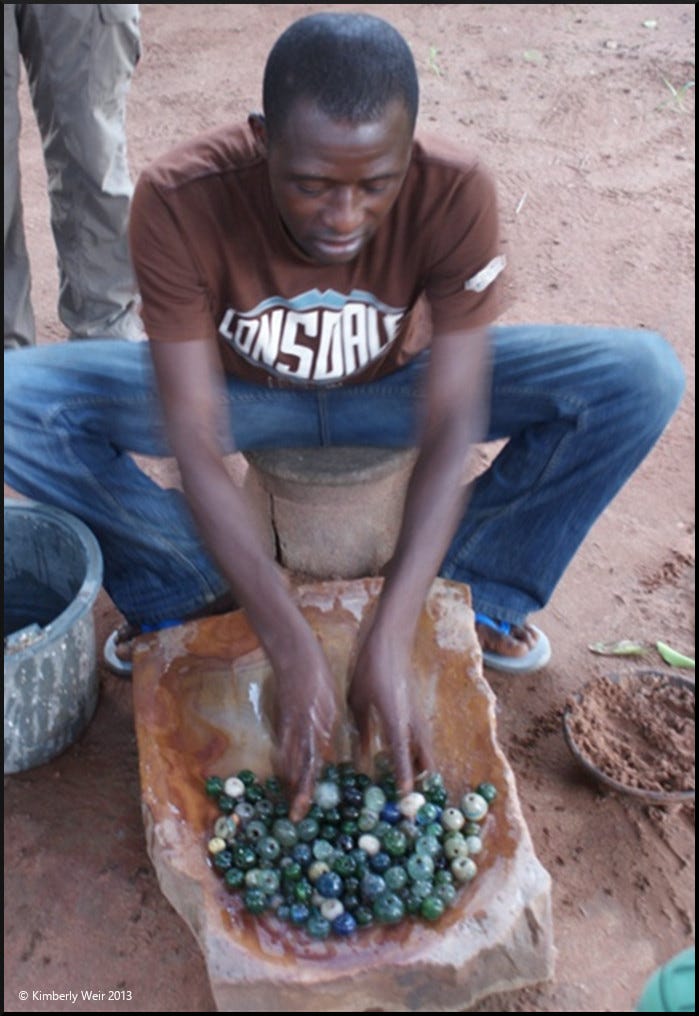

Like Ngwenya, Cedi’s supply comes from the community, paying people to collect clean glass. Therein the similarities end. Cedi built its kilns out of termite mounds, fueling them with charcoal. The process is far more rudimentary, as they hand-crush glass down to a powder with a mortar and pestle. To color the beads, they separate and mix different colored glasses and use local ingredients to make dyes.

Cedi makes their molds out of clay, shape filling-scoops out of repurposed tin cans, and insert twigs into the beads to form holes to string them. The last step is to mix sand with water to smooth them after firing. Except for relying on charcoal which is a very dirty fuel, their bead-making process is maximally sustainable. And though Cedi Beads is a small family-owned business, it pays a living wage to its employees. The owner, Nomoda ‘Cedi’ Djaba, also helped to found Manya Krobo Bead Association to help preserve the local bead-making tradition.

Ideally, all bottles and jars would be collected by the manufacturer to be refilled. Practically, that is no longer feasible in our disposable world—even in developing countries where one would think far more bottles and jars would be ‘R-ed’—reused, reclaimed and refilled, or repurposed before being recycled. The encouraging news is that globally more glass is getting a new lease on life rather than ending up in the landfill.

Thank you for taking the time to read and comment on my post : )

As always, most informative.